Would you call yourself a slow painter? Do you struggle to get enough completed in a 2–3-hour life session? Maybe you find yourself zooming in on detail right away instead of working on the subject as a whole. Maybe you try to see too many color and temperature changes too soon. Before you know it, time's up, but you feel like you've barely begun!

Well, last time, in Improving Your Speed When Painting From Life, I said "You don't have a time problem. You have a goal problem." Overcoming your time problems starts with setting specific, focused goals. Today, I'm going to take that concept to the next level—Your goals may be different depending on what type of life session you're attending.

To conquer the time limit of a life session, you must set a goal that is appropriate for that type of life session.

Today, I'll recommend some goals for two types of life sessions—gesture drawing and portrait/figure painting. When carefully applied, these goals will be a tremendous help in improving your speed when working from life.

Recommended Goals

When Gesture Drawing

In my opinion, your goal when gesture drawing should not be to produce a framable work of art. Sometimes that will happen, but most often it won't. But that's perfectly OK, because producing a framable work of art is not the primary purpose of gesture drawing. Rather, the primary purpose of gesture drawing is two-fold:

- To sharpen your eye for accuracy

- To infuse your drawings with movement and vitality.

Striving for a framable work of art from a gesture drawing session will distract you from the important practice you need. Instead, set a goal that complements the two-fold purpose above. Here are a few examples of appropriate goals when gesture drawing:

- To practice drawing a head in proportion to the body (See Drawing a Head In Proportion to the Body)

- To train your eyes to see the lyrical lines that the human figure naturally creates

- To practice your coordination in drawing lines that are both accurate and lyrical

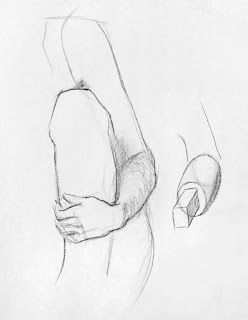

- To practice seeing the subject's forms as 3-dimensional rather than flat (See 3 Ways to Conquer Foreshortening)

(To learn more about gesture drawing, see

Painting Figures That Look Dynamic, Not Stiff)

Painting Figures That Look Dynamic, Not Stiff)

Recommended Goals When Painting

A Portrait or Figure From Life

Ideally, I like to create paintings entirely from life. But for me, this usually requires the model to return for multiple sessions, and sometimes that's difficult. If you only have one session with a model, I recommend that you adopt one of the following goals:

- To start a painting that you'll complete later from photos

(This is usually the goal I set, as I very rarely finish my paintings to a satisfactory degree within the time-frame of a single life session.) - To create a study for another painting that you'll complete later from photos

- To practice on one weak area

(Make this one of the fundamentals—drawing, value, edge, temperature or color.)

As I'm sure you can tell, I'm a stickler for working from life. But photos can be a great aid, and I admit to using them frequently. If you intend to start a painting from life and finish it later from photos, here are a few things you need to know about photography that will help you maximize the time in a life painting session:

- Cameras do a great job of "drawing" (provided you avoid lens distortion)

You should always aim to draw as accurately as possible. But you can save lots of precious time if you remember that your drawing can be fine-tuned later from your photos. In a life painting session, if you can't establish a reasonably accurate preliminary drawing in 25 min or less, I recommend you practice drawing from life with dry media until you can. Becoming more efficient at drawing will free up valuable time to document the other things your camera has a harder time capturing (see 3rd bullet). - Cameras do a great job of capturing detail (provided you focus properly)

I know you know this already, but we all need reminding. Detail should be your very last concern in a life session. It's so easy to waste time caught up in the details—believe me, I know. I suspect this is because we adopt a "walk away with a masterpiece" goal. Capturing detail is something cameras do very well, so take a few photos at the beginning and then make a conscious effort to ignore the details for now. As you paint from life, document the necessities first (see next bullet), and you'll often be pleasantly surprised to find a bit of time near the end of the session to throw in a few details. - Cameras usually do a poor job of capturing values, edges, temperatures and colors the way the human eye sees.

These are the fleeting elements you should use your precious time to capture from life, as they will probably be lost in your photos.

In Summary…

- Your goals may differ depending on what type of life session you're attending.

- Set a goal that is appropriate for that type of life session.

- When gesture drawing, don't expect to produce a framable work of art.

Rather, use the opportunity to practice an area of weakness. - Unless you're able to work on a painting for multiple life sessions, I recommend treating your work as practice or as a study.

- Understand the strengths and weaknesses of photography, and set goals for the life session accordingly.

Dig Deeper in the

Online Video Course!

(Click image to view full-size)

If you found this Free Art Lesson valuable, you'll enjoy digging even deeper in the online video course, Learn to Paint Dynamic Portraits & Figures in Oil. Access to the course will become available for purchase on October 7, 2019, but you can start the course today for FREE! For more information, please click the button below.

|

Does the huge array of paint color options at your art store cause you grief? So many beautiful colors; so little space on one's palette (and often, so few bucks in the art budget). How do you know which colors you really need? That's what I'll talk about next time in The Very Best Color Palette!

—Adam